November saw the release of “Trouble No More 1979-1981,” the 13th volume of Bob Dylan's ongoing “Bootleg Series” of rare and unreleased material. The compositions contained herein caused a lot of confusion and derision at the time since Dylan, born and brought up Jewish, ended 1979 by writing and performing exclusively Christian-based gospel-flavored material. Of course this alienated many fans, though, as with most of his adventures, the public eventually came to accept this phase as one of Dylan’s most creative and intense. Like when he went electric, or threw it all away and went to make some basement noise.

Fans have been so well trained after all these decades that whenever Dylan decides to change directions, most accept that it will one day make sense. As Bruce Springsteen said when inducting Dylan into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1988, “Dylan was a revolutionary. The way Elvis freed your body, Bob freed your mind.”

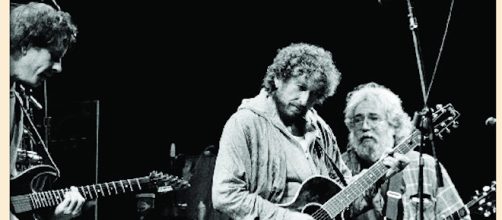

Yes, Dylan's mercurial moves all eventually make sense. Except for Dylan’s collaboration with the Grateful Dead, that is. In between two tours with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Dylan sandwiched in six U.S. stadium dates with the Dead in the summer of 1987. Despite Dylan’s desire to “free your mind,” many fans still cannot wrap their heads around the fact that his interactions with Jerry Garcia specifically, and the Dead in general, were instrumental in getting the iconic singer-songwriter back on track after losing his way in the mid-1980s.

In his somewhat fictionalized memoir, “Chronicles, Volume One,” Dylan did not give direct credit to Garcia for his friendship and support, but instead used a made-up story in which he left tour rehearsals, frustrated, to find inspiration in a phantom jazz singer at a local club. This did not help fans understand the importance of Garcia’s impact, nor did the unrepresentative 1989 live document, “Dylan & the Dead.”

Dylan and the Dead

Howard F. Weiner’s most recent book, “Dylan & The Grateful Dead - A Tale of Twisted Fate,” may change those fans’ minds. Though Weiner has written numerous books about Garcia, the Dead, and Dylan, and has an intense knowledge of the artists, he’s a bit more in the Dead camp, his first love.

Yet it's Weiner's latter day enthusiasm and exploration of Dylan's work that gives the narrative a unique and passionate perspective. “Dylan & The Grateful Dead" reads like a print version of a Grateful Dead bootleg tape, as his expertise enables him to interweave the disparate yet parallel stories of Dylan and Garcia like a particularly inspired “China-Rider” jam.

The story as it unfolds in “Dylan & The Grateful Dead” begins to resemble a biblical parable, or maybe a Greek curse. When Dylan and the Dead crossed paths in 1987, the Dead were about to reach their commercial peak with the release of their “In The Dark” album, with their surprising MTV-friendly hit, “Touch of Grey.” It was the Dead’s first album of new material since 1980’s “Go to Heaven.” In the interim, the band was so studio-phobic they begged their label, Arista, to accept two double-live albums in exchange for their next contracted studio one.

1987 tour

The Dead was becoming such a touring behemoth, with tribal fans following them around the country, Ticketmaster created a unique database to handle the intense demand. In the mid-1980s, after alienating much of his fan base yet again, Dylan needed Petty on the bill to help him fill up bigger venues. The collaboration between Dylan and the Dead led to a creative explosion. The Dead had almost become a Dylan cover band by this time, while Dylan, himself, was at a crossroads. During rehearsals for 1987’s “Dylan & the Dead” tour, Garcia guided a dispirited Dylan into reconnecting with his own catalogue. In the studio, with help from the Dead’s Bob Weir and Brent Mydland, Garcia backed him up on a much needed radio hit, “Silvio,” co-written by Dylan with Dead lyricist Robert Hunter, a highlight on the lackluster album, “Down In The Groove.” Meanwhile, as the Dead’s shows were getting bigger and more unwieldy, Dylan purposefully decided to model his so-called “Never-Ending Tour” after the Dead’s touring philosophy.

This meant mixing up the set lists every night and touring throughout the year, regardless of any new album promotion or other expected commercial concerns.

Dylan, however, decided to downsize and often play smaller venues, attempting to destroy the myth he helped cultivate. It gave him an alternative career path, one which would not ultimately threaten to do him in. Simultaneously, Garcia was trapped in the role of cash cow, responsible for generating income for the entire extended Dead family. Weiner discusses Garcia’s dilemma in great detail, and is one of the book’s many strengths.

Garcia, Dylan, and Presley

By burning bridges, Dylan has been able to survive. Garcia was unable to break away, and, much like Elvis Presley, self medicated to help cope with the immense pressures, demands, and lack of control, in his own life.

Even though neither sang their own lyrics, Presley and Garcia were worshipped for the images they projected, or more accurately, the ones fans wanted to see. Apparently neither musician was ever able to extract themselves from “the star-making machinery behind the popular song,” as Joni Mitchell once wrote.

Presley died at 42, while Garcia barely made it to 53. Dylan learned his lesson in 1966, aged 25, when he used a motorcycle mishap to put the brakes on his career. He stopped the world and got off. Dylan is now 76, still on the road, heading for another joint. As much as possible in this industry, he controls the shots.

Dylan’s collaboration with Garcia and the Dead was one of the most important, and inspiring, associations in his career. Tragically, Garcia was not able to learn the most important lesson he could have learned from Dylan. Weiner’s “Dylan & The Grateful Dead” will help you understand why.

“I will survive,” indeed.