Not all art news stories are newsworthy. Sometimes it’s their backstories – often unheralded – that provide crucial information.

Consider the bulletin that Renaissance painter Andrea Mantegna’s portrait “Saint Sebastian” is on its way from Venice (Ca’ d’Oro) to Paris (Hotel de la Marine) for a first-time show. The Italian museum needed to closed for renovation.

How newsy is that?

Just because this portrait never left Italy since it was painted strikes me as trivia. But then again, how it was painted is the story worth telling. Have you seen this thing?

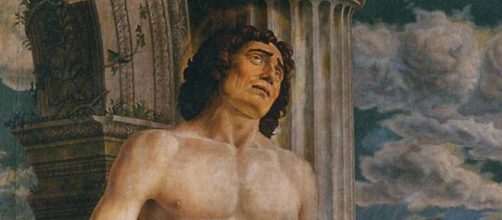

"Saint Sebastian" is a painting with the density of stone. Yet, despite its resemblance to a carved boulder, it conveys the feelings and frailties of a human being.

Pierced by arrows, Sebastian’s agony is so marked on his face that you imagine hearing him groan. It’s his suffering face that enlivens an otherwise ossified-looking face.

As you may know, Sebastian was condemned to death but he didn’t die from the piercing arrows. His martyrdom came when he was clubbed to death and tossed into a sewer.

Maybe because of that ignominious end, Mantegna painted Sebastian like an impenetrable and everlasting monumental sculpture.

The back story

According to Mantegna’s history, the look of sculpture in his paintings was a historical inevitability.

His training as a painter focused on the study of ancient Greek and Old Roman sculpture, which he grew to love.

Historian Giorgio Vasari explained the painter’s love of ancient sculpture in his 1550 book "The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects" saying that the painter held the opinion that the statues in antiquity were more perfect than anything in living nature.

But Mantegna took hits for letting ancient sculpture influence his painting. Even his art teacher, Jacopo Squarcione, publicly berated him for it.

Squarcione contended that Mantegna’s paintings were inferior because he copied from marble statues. And, since the stonework was hard and human flesh was soft, he couldn’t possibly capture a likeness of the human form.

But wait, only a century later, Peter Paul Rubens did the same thing – paint the human form from ancient statuary without a peep from anybody in the art world.

And Rubens is the last person you’d expect to use that method. After all, he’s known for flushed, fleshy figures – muscled men and well-endowed women. That his models were often antique marble statuary is unexpected.

Rubens’ models are all the more surprising given he penned a treatise warning artists against copying from statues. He said it would be harmful to painters who don’t distinguish stone from flesh.

To help artists make that distinction, Rubens advised adding dimples and avoiding the harsh light that comes from the stone’s luster.

Sad to say, Mantegna was intimidated by his teacher’s criticisms and began to paint from live models. Vasari said he made so much progress that his life drawing became as effective as his derivations from sculpture.

But Mantegna never stopped believing that statues of antiquity were more perfect. Vasari recorded the painter’s thinking this way:

“The sculptors of the ancient world had used several living models to create the perfection and beauty which nature rarely brings together in a single form: They found it necessary to take one part from one body and another from another.”

While Mantegna’s fondness for the ancient aim for perfection is reflected in his work, the suffering face of Sebastian did not come from any historical object. It came straight from him.