From merry old England comes “The Color of Anxiety,” a show of Victorian sculpture that inadvertently calls up the anxiety of Meghan Markle. (I’ll get back to that in a moment).

The exhibit at the Henry Moor Institute in Leeds tells the story of the end of whiteness in sculpture (a throwback to ancient Greek marble), and the rise of color in 19th-century England.

This change came about when photographs of distant lands moved British artists to gild the lily, so to say, and use materials like silver, gold and bronze.

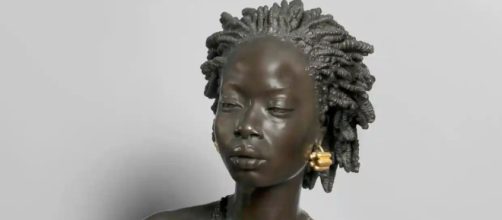

“Venus Africaine,” a bronze work by Charles Cordier, typifies the jettisoning of white marble.

Additional color can be seen in the gilt earring and coral beaded necklace.

As sculpture changed its complexion during Queen Victoria’s reign, she clearly enjoyed the view having bought “Venus Africaine” as a gift for her husband Prince Albert. King Charles inherited the work and keeps it in the Royal Collection.

Sign of the times

One may wonder what Queen Victoria would say about a colored person worthy of inclusion in a royal art collection, but not in person. I’m thinking of Meghan telling Oprah Winfrey of a royal fretting that her mother’s dark skin might end up in her son and prove “too dark to represent the UK.”

Talk about representing the kingdom. “Venus Africain” bears something else observable besides skin color.

The sculpture speaks, consciously or unconsciously, of England’s slave trading.

The model for this sculpture looks to be suffering from anxiety of her own, listing to one side as if in pain. Unlike the traditional full-length renditions of Venus seen throughout art history, this one is cut in half.

What’s more, while a cloth covers her anatomy, it has the look of a binding. Her arms, held behind her back, add to that impression, as though she’s being held against her will.

As a result, “Venus Africaine” is a picture of a black slave rather than a Venus. What, you may ask, was Queen Victoria thinking buying this? Sign of the times. Black slavery was as much the fashion of the day as crinolines and hoop skirts.

In fact, the slave trade in Victoria’s time was so big that historians Barbara Solow and Stanley Engerman credited it for financing the Industrial Revolution in their 2004 book “British Capitalism and Caribbean Slavery.”

Given that the slave trade was the way of life back then, the queen might get a pass for not noticing the tragic air to “Venus Africain.” But that was then, and this is now, and her progeny must surely know the kingdom’s history of cruelty to people of color.

Or do they? What explains the concern that Archie’s skin might prove “too dark to represent the UK”? Apparently, heritage, even if it’s racist, is a hard habit to kick in England.

You may remember a story I noted in 2020 about a 55-foot-long mural in Tate Britain restaurant painted nearly a century ago.

It plainly pictures the mistreatment of little black boys.

The mural shows a well-dressed white woman yanking a roped small boy struggling to keep up with her. There’s also a second boy with a collar around his neck running to keep up with a horse-drawn cart driven by another white woman.

Heritage vs. Humanity

Despite the many complaints about this mural, the Daily Mail cites a museum statement that says the mural is “a work of art in the care of trustees and should not be altered or removed.” Let’s hear it for England’s art heritage.