An Atlantic Magazine story of memorable food scenes in literature, like John Updike’s character Rabbit Angstrom favoring candied yams, has me thinking of unforgettable food scenes in painting.

Focus on food in painting traditionally came in the form of still life, a genre low on the totem pole for a long time in the art world. But no more.

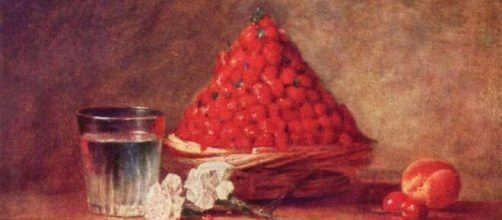

In the news is 18th-century artist Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s painting "Basket of Strawberries," recently auctioned in Paris for a record $26.8 million – the most expensive still life ever sold.

But it’s hard to see why this work broke all records when compared to still life paintings in the century before Chardin’s made by women.

(More about that in a moment).

There’s little to admire in Chardin’s strawberries. What you see is the fruit piled high to form a cone shape. Their color is juiced up to contrast with a nearby peach and cherry. There’s just nothing picturesque about a mound of berries.

Hunger games

Yet, this work is so treasured that it’s being fought over. Just last week, Art News reported that its sale to New York art dealer Adam Williams was blocked by the Louvre.

The museum couldn't afford the purchase but claimed that no one else should buy it, either owing to French law that says a national treasure can’t leave the country.

Blocking by the Louvre will hold for two and a half years at which time the museum hopes to have the necessary funds for the purchase.

Other countries have similar laws to prevent artworks from going to other lands. England, for instance, recently kept the export of Joshua Reynolds’ "Portrait of Omai," saying it was “of outstanding significance.”

But I fail to see the “significance” – outstanding or otherwise – of Chardin’s stack of strawberries. Besides, it's not like the Louvre is Chardin-impoverished, already owning 41 other paintings by the artist.

Cherche la femme

Of course, the thing that galls is that still life paintings by female painters don’t have the currency that Chardin’s strawberries have.

I’m thinking of Fede Galizia’s "Peaches in a Porcelain Bowl," painted in 1607. It’s not even held in a museum or public collection, but rather owned privately.

As far as I’m concerned, Galizia’s peaches best Chardin’s strawberries.

You have only to look at her rendering to imagine feeling their fuzzy skin.

I’m also thinking of 17th-century painter Louise Mollion's still life paintings that capture the very texture of water droplets. Clearly, the 17th century wasn’t a good time for still-life painting. The French Academy made sure of it by decreeing such art unimportant.

Or was it only because these less ballyhooed still life pictures were made by women? How else to understand why Chardin’s work is so valued? And not just his.

Consider "Apples and Oranges" by Paul Cézanne held at the Musee d’Orsay in Paris. This museum tags it as “the most important still life produced by an artist in the late 1890s.”

Maybe Galizia and Mollion were born too soon.