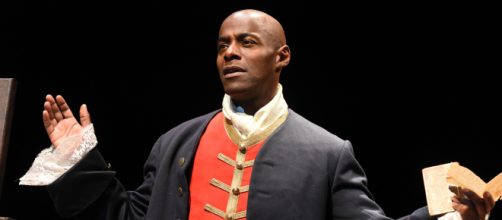

“Sancho: An Act of Remembrance” is a play that chronicles the life of an African man named Charles Ignatius Sancho. Born on a slave ship, Sancho became known as a composer, social satirist and—above all else—an abolitionist. He was regarded as a man of the refinery in English society during the 1700s and, in 1774, he was even the first person of African descent to cast a vote in an English election. Famed artist Thomas Gainsborough painted Sancho, and he was known for his plays, poems, and music. A financially secure householder, Sancho socialized with artists, intellectuals, and constantly challenged the status quo.

The one-man show is a comedic and witty retelling of Sancho’s extraordinary life and how he rose above the issues that faced him such as xenophobia, poverty, and prejudice. The play is presented by The Classical Theatre of Harlem and will run from April 18 to May 6, 2018, at The National Black Theatre in New York City and London’s Wilton Music Hall from June 4 -16, 2018.

Creator Paterson Joseph recently discussed his experiences working on the show, inspirations, and more via an exclusive interview.

Plays, theater, and history

Meagan Meehan (MM): What prompted you to get into the theater and how did you break into the very difficult performing arts industry?

Paterson Joseph (PJ): As I write in my new book “Julius Caesar & Me,” I was not destined for a life in art.

My obsession with language came early as my working-class, Caribbean parents stopped speaking St Lucian Kweol in our London home when I was three years old. I listened so carefully and read so assiduously that it was no surprise that I was hooked on Shakespeare from the first time I read his work - on my own - with no instructions, as a teen.

Youth theatre was my access point. That’s why I am a fierce advocate of these groups. They not only took me and my contemporaries off the street but gave us an artistic voice. I was at The Cockpit in Marylebone with Lennie James. Twenty-odd years later I know that Daniel Kaluuya experienced the same thing at Hampstead Theatre.

We need more of these groups.

MM: When did you first hear about Charles Sancho’s life and what about it most fascinated you?

PJ: So, it’s either Charles Ignatius Sancho or Ignatius Sancho; ‘Sancho’ is actually a nickname. Honestly, I feel ashamed to say this, but it was in the year 2000! It is amazing to me now that I hadn’t even been aware of a major figure in history like this. And that knowing there had been over 10,000 Afro-Britains in 18th Century England, his name had not popped out. I have author Gretchen Gerzina to thank for introducing me to him through her brilliantly researched book “Black England” (the US title is “Black London”).

I was fascinated by his depiction in the 1768 portrait by Thomas Gainsborough.

I thought it might have been one of the artist Hogarth’s satirical prints showing what an African Gentleman might look like if given the equal opportunities of his white contemporaries. A positive but imaginary piece of anti-slavery propaganda.

I was excited and humbled to learn that Charles Ignatius was a real man. But you know what really caught my eye about him was not his political activism - which was less vociferous than his younger counterparts Olaudah Equiano and The Sons of Africa - but his ordinary domestic life. His struggles to keep body and soul together in a sometimes hostile London was quietly heroic to me. His Jamaican wife Anne Osborne and his kids - “my little Sanchonettas” - I include in this heroic, pioneering narrative.

MM: How much research went into the writing of this play and how did you infuse the humor?

PJ: So many years of immersive research went into “Sancho - An Act of Remembrance.” I started around 1998 and finally finished a performable draft in 2008. I started with scraps from the internet. There really is so much more out there now than they used to be. Then I read his letters published by Penguin books. There are so many of them it took me months to get through them. I read the writings of Samuel Johnson his contemporary - and nearly biographer - thoroughly. I read James Boswell extensively, who was a companion of Samuel Johnson and knew that world of 18th Century literary figures.

It was important to me to get the wit and the syntax and grammatical turns of phrase that governed 18th Century literary practice.

As for his humor which suffuses his letters, the wit and speed of thought were plain from the very first letters. His voice is clear to me. Particularly the way letter writers in his day made light of the hardest times. Even the deaths of several of his children never lead him to indulge in melancholy. Extraordinarily hard to penetrate this epistolary, distancing style but I hope we can see in Sancho the shade as well as the light behind his sometimes defensive, sometimes subtly aggressive wit.

Acting, performing, and the stage

MM: This is a one-man show, so was it tough to convey such a rich life as a lone actor on stage?

PJ: Frankly, I wanted to keep it simple. I feared having a full-blown play, with a large cast, would risk obscuring the man himself.

I first conceived the idea of the play, as an audience with … in other words, a way of meeting Sancho one-on-one. He was so unknown to many that this felt like the best way to introduce him to a world ignorant about him and his world. The worst part of performing a monologue is that Billy-no-mates moment backstage when you have to pat yourself on the back to say, “well done, me.”

MM: What was it about Charles that most appealed to people and why do you think this story resonates so well today?

PJ: His personality reaches out from the stage via his open-hearted nature. His lack of indulgence in a time of harrowing, brutal cruelty being perpetrated on African peoples all over the globe including in Africa, the Caribbean, and The Americas is admirable and deeply endearing.

We appreciate his self-control and feel his frustration at the injustice of his situation all the more since he never allows himself to express self-pity.

In Washington, at the Kennedy Center, we heard from women and men who had lived through the 1960s and 1970s Civil Rights eras how Charles Ignatius’ story was still their present-day story. Voter photo IDs, they informed me in my woeful ignorance, was disproportionately disenfranchising ethnic minorities, particularly African Americans. I was outraged and determined to help. The voter registration drive after each performance at The National Black Theater is our little bit of push-back.

MM: What’s your favorite part of the performance and why?

PJ: The talkback! Seriously. I know and love every inch of this labor of love, of course. However, I’m much, much more excited by the live feedback my attentive audiences bring to the post-show question and answer session.

MM: What has preparation been like?

PJ: I spent a great time recently performing Sancho and talking to students and faculty at the University of Texas at Austin. I hadn’t performed the show for nearly two years. So, it was gratifying to find that Sancho was only a quick refreshing line-learning session away. He was still in my head! In fact, I had lines to learn for the TV series “Timeless” but had to stop while I was performing Sancho as he kept creeping into my character ‘Connor Mason’s’ delivery.

Incongruous, having an 18th Century sensibility in a modern sci-fi show.

MM: What do you hope people take away from this show and what else is coming up for you?

PJ: I want the audiences in Harlem to recognize themselves in their Black British counterparts. The African Diaspora in London at Wilton’s Music Hall this June will with any luck get a sense of their Belonging in their own country. Not something that we all feel or know with any confidence as we speak. Knowing Sancho and his black contemporary’s stories have caused me to hold my head a little higher than normal in the UK and beyond. Know your history. Know yourself.