Imagination wasn’t always visual art’s claim to fame. At first, it was a utilitarian thing, made for practical purposes. When cave people hunted game, they pictured the chase on their stone walls and prayed over them for food. The Old Nile people painted their lives on tomb walls to ensure life after death. And painting in the Middle Ages was dictated by the church. Art was set free in the Renaissance and painters like Piero di Cosimo could show the world what a creative mind could do.

The meaning of art

Cosimo was one of the earliest to paint his flights of fancy.

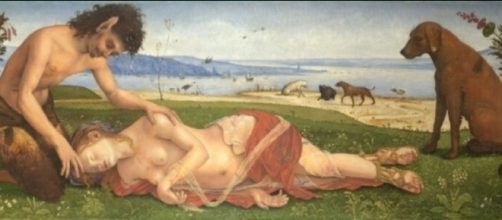

Consider “A Satyr Mourning Over a Nymph.” Some say the image is based on Ovid’s Metamorphoses. If not that, what does the picture mean? Whatever you think it does. Interpretation is the name of the game, and if you don’t want to play, that’s OK. Just don’t say you can’t understand art. That’s like saying, you can’t think for yourself. On Friday, the Guardian, a British daily, featured the “Satyr painting in London’s National Gallery as “masterpiece of the week.” Cosimo is worth discussion.

Bad mouthing an artist

Sad to say, historians haven’t always treated Cosimo well, and one of them surely should have known better. Giorgio Vasari, who knew the artist, felt it necessary to report on his quirks and what a kook he was in his chronicle “The Lives of the Artist.” He cited things like how the painter subsisted on hardboiled eggs alone; although he managed to mention the poetic quality of his work and his imagination – but almost as afterthoughts.

Surrealism before its time

Cosmo’s imagery is so out of the ordinary that it borders on Surrealism long before there was any such thing. I’m thinking of “Allegory,” a vision of a white horse, a winged woman holding the horse with string and a mermaid. Clearly, he liked Greek mythology a lot and also had a dark side. But despite the foreboding in his work, he also showed his soft side. “The Visitation with St. Nicholas and St. Anthony Abbot,” tells the story of the Virgin Mary finding out about her pregnancy from her cousin Elizabeth and described her in a way other painters usually haven’t He showed her state of wonder. It goes without saying that Cosimo was true to the Renaissance. He paid attention to states of mind.

Getting proper credit

All that said, what you often get from art history are Cosmo’s unusual ways. Vasari once made a point of saying that the artist was so absorbed with his own thoughts that when talked to, he had to be told everything twice: “If Piero had not been so abstracted... he would have won recognition for the great talent he possessed, whereas through his brutish ways he was rather held to be a madman.“ Not today, he’s not.