When starting out, most artists struggle for a shot at success. Rough starts hit even those now celebrated. When Monet first exhibited his painting “Impression – Sunrise,” it was ridiculed. Louis Leroy, art critic at the time, aghast that the painter spurned traditional picture-making techniques, slammed his gauzy image as a mere impression. He meant it as a slur, but it ended up classifying one of the most popular art styles of all time. And Vermeer, famed today for “Girl with a Pearl Earring” and other everyday subjects, was hard up for commissions and forced to borrow money to support his wife and children and need his mother-in-law to guarantee the loan.

Then there was Van Gogh who couldn’t sell even one painting except whatever his brother Theo bought. It’s a long haul for most artists, which is why dream dreamt by them that come true warrant attention.

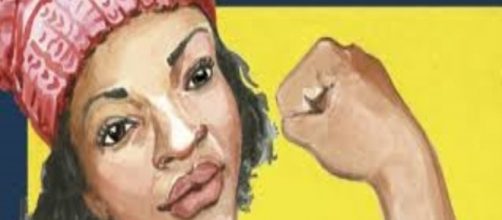

Feminist icon is back

Meet Abigail Gray Swartz, a freelance illustrator, and mother of two out of Maine who was looking for a break and got it when one of her works made the cover of The New Yorker magazine. On the Feb. 6 issue, subscribers saw her image of Rosie The Riveter, the graphic symbol of female factory workers making munitions in WWII now updated as a woman of color.

Swartz took her inspiration from the Women’s March on Jan. 21 that drew 3 million worldwide to protest Trump’s denigration of women.

To make The New Yorker cover is like a pop singer making a hit record. “It’s been a longtime dream to work for them,” Swartz told the Portland Press Herald. “So I am pinching myself now that it has happened...I was just blown away and really happy.” She had submitted her idea for cover art to the magazine without any expectation of an answer.

Pictorializing a protest

But the magazine’s arts editor, Francoise Mouly, who received many ideas for a cover design having to do with the Women’s March, was taken by what Swartz sent her{ “She shaped it in a way that took it one step further than the others.” The step taken - picturing the woman as black - made the old-time icon contemporary. The original Rosie was a white woman created by Pennsylvania artist J.

Howard Miller who was tasked with recruiting females for factory work making war supplies while men were at war. Swartz felt tasked, too.

“Art and artists are very necessary, especially during times of turmoil,” she said. “I want to do good with my art, be it to inspire people or lift them up.” And it looks like others have the same impetus. Swartz noticed that protest signs are moving from word communication to the “conceptual and visual“ variety. “Along with the traditional messages scrawled on boards, we’re seeing some really strong graphics.” Check hers out. On her Twitter page, the artist lists herself as a children’s book illustrator. This is reflected in her version of Rosie the Riveter, which is distinctive for its refreshing clarity, simplicity, and honesty.