Amateur Astronomers are famed for making celestial discoveries, especially comets, since the time of the first comet hunters, the French, Charles Messier (1730-1817) and his contemporary rival Jean-Louis Pons (1761-1831), the fashioned way of looking through the eyepiece, visually, for the last 3 centuries. The sport continued through the 19th and 20th centuries with various nations producing their passionate comet hunters. But this is the digital era, and today 21st century amateurs employ digital technology to hunt new ones in the sky.

While professional astronomers specialize in cometary physics and dynamics, they are more responsible for studying cometary astrophysics.

Amateurs are the content ones spending nights peering for finding the 'next one', an unknown comet. Together, through this 'pro-am' collaboration, science is complimented.

C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy)

One name that stands out – and very successfully at that – is of the Australian Terry Lovejoy. An expert digital comet hunter, he uses an 8-inch reflector with his ccd camera (earlier dslr camera) to scan regions of the sky. Credited with 6 comet discoveries between 2007 and 2017, one that remains remarkable in terms of cometary science is his 3rd Discovery, C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy), made on November 27, 2011. Terry had discovered a Kreutz Sungrazer type comet from ground. These are peculiar comets that are characterized by orbits taking them extremely close to the Sun at perihelion (closest point to the Sun during its orbit around), on most occasions above the boiling solar surface.

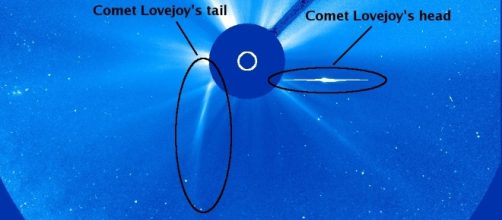

Such passages are open laboratories for professionals to inherit more on comet behaviours under unnatural circumstances without sending any spacecraft flybys (as in case of Comet 1P/Halley and Giotto, or Deep Impact Mission and Comet 9P/Tempel-1). The available resources can be well utilized, in this case NASA-ESA's Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) and NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), who are already at a vantage to observe anything solar. There were other 3 solar-dedicated spacecraft which were in the armada: twin Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) probes, and ESA's Proba-2 microsatellite. However, SDO was the one giving professionals the most dramatic footage of their first look at the bright comet traveling through the Sun's atmosphere.

Comet Lovejoy was calculated to pass only 120,000–140,000 km above the seething stellar surface, typical for a Sungrazer. We were going to clearly see this episode in intricate detail through the spacecrafts' high resolution cameras. (I remember) All bets were on the comet disintegrating as it dashed above the violent, raging solar surface, through its hot atmosphere, whilst perihelion – where the temperature reaches over a million degrees Fahrenheit. After emerging from perihelion it was expected there would be no remnant of the cometary coma, for obvious reasons. But as the renowned comet hunter / discoverer David Levy had phrased long ago, "Comets are like cats: they have tails, and they do precisely what they want", C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy) gave a stunner to professional astronomers.

It did what it could not have, should not have. It survived the brutal perihelion passage! After survival, however, the comet underwent major changes, like permanent loss of nuclear condensation, formation of spine tail, and a severed head (coma) with no tail. The head did disintegrate sooner, the process which culminated with an 'outburst'. It was a new inheritance on behaviour of tails and comae of sungrazers, and the effects of solar interaction.

C/1965 S1 (Ikeya–Seki)

Rewinding back over half a century ago, it were the legendary Japanese amateur comet hunters, Tsutomu Seki and Kaoru Ikeya who made a splendid find – again a Kreutz Sungrazer – in form of C/1965 S1 (Ikeya–Seki), which went on to be the brightest comet of the 20th century!

Observing independently on the night of September 18, 1965, what the young amateurs had discovered as part of a systematic visual comet sweep was called "The Great Comet of 1965". So bright it was that the comet was clearly visible in the daytime sky next to the Sun during its perihelion, with descriptions like “it was 10 times brighter than the full Moon”!!

This one came within about 450,000–650,000 kilometres of the Sun's surface. This one, too, made through perihelion without disintegrating, but the main nucleus fragmented owing to tidal forces induced by its proximity to the Sun. An extravagant tail was reported post-perihelion on October 21, 1965, for next several days, with reported sightings of the splendorous comet in daylight.

In the case of these two sungrazers, they were larger bodies, therefore they managed to withstand the fiery ordeal. But thats not the typical case with almost all other sungrazers, which are much smaller than these two, spanning only a few metres across. They never make through, getting totally obliterated. You could say these two, in our feature, were the exceptions. Nine major sungrazers were seen between 1843 and 2011.

Other Instances

We have looked at only 2 comets, not covering the other discoveries like the historic Comet D/1993 F2 (Shoemaker-Levy 9) discovered by the legendary couple-team of David and Wendee Levy and Dr Eugene and Carolyn Shoemaker, which collided onto Jupiter in July 1994 and gave scientific humanity an eye-opener on the magnitude of cosmic catastrophes that we had never directly witnessed.

Such amount of professional astronomy is always learnt when any astronomical events make their way in the sky. And most of the times it is amateur astronomers – those like you – who have found that and endowed to the scientific fraternity at-large. Amateur astronomers continue to fascinate us with their sudden gifts, say, in form of bright comets. And as statistics go, we dont fail to see one bright every decade, on average.