Is violent behavior our new normal?

A 17-year study conducted by the New York State Psychiatric Institute concluded in 2002 that adolescents and young adults who watched TV for more than seven hours a week had an increased likelihood of committing an aggressive act in later years.

Question for the ages

Given the rash of mass shootings in the U.S., have the chickens come home to roost? The Psychiatric Institute should also study the long-term effect of museum-going. I’m thinking of “The Murder of a Woman,” a painting by Oskar Kokoschka, and “Blood Is the Best Sauce,” a drawing by George Grosz at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

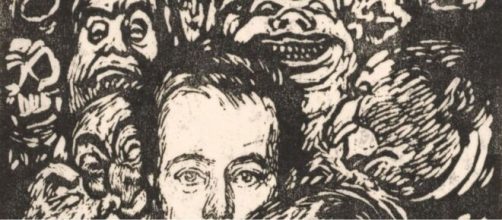

The LACMA exhibit is all about German Expressionism and the show titled “Reexamining the Grotesque” – doesn’t shy from its monstrous imagery.

In the spirit of the show title, let us examine the grotesqueries in the art of Kokoschka and Grosz, beginning with "The Murder of a Woman."

The painting describes a male raising his fist to a nude female struggling to avoid his blows. There’s also a fair amount of spilled blood in the scene.

You may well wonder what drove Kokoschka to picture a man beating a woman to death? His biographer Frank Wilford suggests an answer in his 1986 book “Oskar Kokoschka, A Life.”

Wilford noted that the painter had ordered the manufacture of a life-size female doll to serve as his companion.

The doll was made in the image of Alma Mahler, the wife of composer Gustav Mahler, whom the painter wished was his.

In apparent frustration, Kokoschka ripped the doll’s head off and tossed the decapitated body into his front yard. In his letters later published he wrote without shame of what he had done, even adding how the doll was “drenched in blood.”

Clearly, “The Murder of a Woman” bears some connection to his beheaded doll. And just as clearly, Kokoschka wanted his viewers to feel the full impact of his work.

The artist wrote to art historian Hans Tietze about getting to the essence of his subjects “with such elemental simplicity, that one principal line makes one forget the chance elements that were omitted.”

Mission accomplished

Kokoschka’s “principal line” describing a man raising a fist to a woman while his other hand holds down her head is hard to forget.

Historians have made excuses for Kokoschka’s bloodlust. Ian Chilvers wrote in his 1988 book on art and artists that the reality of World War I pulled the painter from realism to psychological portraiture. PTSD?

Is that what also propelled George Grosz to draw “Blood is the Best Sauce”? According to LACMA’s website, the answer is yes, as it describes the grotesque in the exhibit as “a persistent undercurrent in German art of the early 20th century.”

“Blood is the Best Sauce” could serve as an anti-war poster. Grosz makes the case with his image of a foot soldier mindlessly bayonetting a civilian while fat cats – presumably politicians – wine and dine.

Grosz left Germany in disgust with the corrupt ways of Berlin society and its politics during World War I.

Historian Wolf-Dieter Dube acknowledged that the painter felt bad about being German.

In Dube’s 1972 book “The Expressionists,” Grosz is quoted saying: “Man is a beast.” He also said he preferred the America he saw in James Fenimore Cooper’s historical novel.

Grosz admired American lore even as a boy. At nine years old, he copied down Cooper’s “The Last of the Mohicans.” It was a borrowed book and because he had to return it, he made himself a copy.

In Grosz’s "An Autobiography," he said he copied the book in his “very best handwriting. I love those Indian stories so much that I wanted to have them for myself, to read whenever I wished.”

Of course, the America Grosz loved is fiction. The mass shootings and police slaying of black men in the U.S.

are as bestial as man’s inhumanity to man is anywhere else.

But here’s the thing. Will the LACMA visitors read all the art historians’ rationales for picturing violence? Or will impressionable souls see assaults as acceptable owing to their presence in the polite society of an art museum?