What makes good art good? The short answer: It’s not Andy Warhol’s “Marilyn,” and it’s not Louise Bourgeois’ "The Good Mother." Both were in the news this week, prompting my question.

First is the Warhol news. Last week, after only four minutes of bidding, Christie’s New York sold the Pop artist’s portrait of Marilyn Monroe for $195 million. In four minutes!

“Marilyn” became the most expensive artwork ever sold. The previous record of $179 million was set in 2015 by Picasso’s "Les Femmes d’Alger."

Does valuing “Marilyn” over "The Women of Algiers" mean anything?

Is Monroe’s portrait the art world’s magnum opus? Is the portrait good art?

No, no, and no

Yes, and yes, says Alex Rotter, chairman of 20th and 21st-century art at Christie’s, if you’re talking about the 20th century: “The painting transcends the genre of portraiture, superseding 20th-century art and culture.”

How can Rotter believe that? Warhol’s portrait transcends nothing.

This is a good place to start my answer to the what-makes-good-art-good question. Rotter noted one of the ingredients: it transcends. Does anyone really think that “Marilyn” will speak to people in the future?

Good art comes down to its capacity to transcend time and continue to impact centuries later when no one is clued into the celebrity of Monroe or Warhol.

Another ingredient. Good art needs metaphor to allow meaning beyond what you see. Making images too literal keeps viewers from connecting with their own experiences. “Marilyn” is too unambiguous.

About Bourgeois

In London, the Hayward Gallery has just mounted a retro of Bourgeois’ psychologically charged sculpture. But they're too explicit to be called art.

It doesn’t let you come to it on your own. It tells you what to think. It’s too specific.

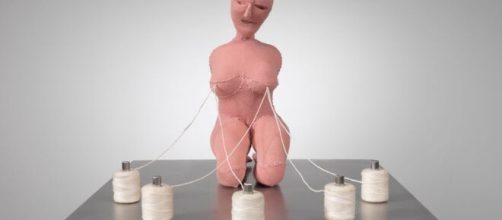

Consider “The Good Mother,” made 30 years ago when women’s bodies still belonged to them. You’d think it was made this month by the look of this work.

What you see is a female without arms, suggesting a lack of volition, and kneeling as if pleading to be free of the ties that bind her – in this case, five spools of twine roping her in.

Granted, "The Good Mother" transcends like crazy. But it’s too documentary to be called good art.

Obviously, the Bourgeois wasn’t thinking of Samuel Alito’s zeal to rescind Roe v Wade. He wasn’t even on the court when she created the sculpture. She was simply conveying her experiences as a parent.

At least she was conveying something. What does Warhol’s portrait of Marilyn convey? With hair dyed yellow, with blue shadowed eyes, with mouth rouged with lipstick, what you get is an ad for Clairol and Revlon.

If only Warhol had captured Marilyn in her last movie, “The Misfits,” in 1962. She played a newly divorced woman who found comfort with an aging cowboy, played by Clark Gable.

Monroe’s playwright husband, Arthur Miller, wrote the script for her.

And she enacted it so movingly that she looked as if she would shatter at any moment like some fragile crystal stemware dashed to the ground.

Her performance was enough to make you tear up, which goes double for Bourgeois’ "The Good Mother." But is any of this good art? You have my answer.