A $5 million research center focused solely on Henri Matisse is opening at the Baltimore Museum of Art in Spring 2022. Here’s hoping the research will turn up all the dumb things he said.

(More about that in a moment).

Sometimes I think that artists shouldn’t talk and just do their work. Consider what Edouard Manet said to writer George Moore about Impressionist Berthe Morisot, who was married to his brother: “My sister-in-law wouldn’t have been noticed without me.” (Really, Ed?)

Say what?

Speaking of Impressionism, Renoir’s dealer, Ambroise Vollard, documented him putting down the style he’s famed for: “In a word, Impressionism was a blind alley, as far as I’m concerned.” (Now you tell us).

Then there’s portrait painter Thomas Gainsborough telling his friend, conductor-composer William Jackson, “I’m sick of portraits... and wish very much to walk off to some sweet village, where I can paint landscapes.” (Who’s stopping you, Tom?)

And here’s my all-time favorite art speak. It’s from the bio “Jackson Pollock: An American Saga” where historians Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith noted an incident that ought to go down in infamy.

Pollock was flinging a stream of paint from the end of a stick at a canvas when a woman asked, “How do you know when you‘re finished?” He replied, “How do you know when you’re finished making love?” (Apples and oranges, Jack!)

So, when the Smithsonian magazine said the Baltimore Museum’s new research center would entail a dedicated exhibit space, library, and study room just for Matisse, I had to wonder if at least some of the contradictory statements from him will surface.

I’m thinking of all the bon mots in “Notes d’un Peintre,” such as saying that in his paintings, he “dreams of serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter.” He called such pictures “mental soothers, like a good armchair in which to rest from physical fatigue.”

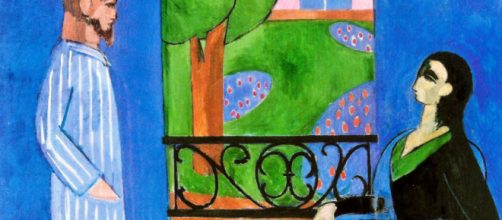

To further his point, Matisse offered an example of soothing: the “gossamer look of a woman’s dress that slips from her shoulders.” But soothing is not what you get in a portrayal of himself, and his wife Amelie Parayre called "The Conversation."

Dream on, Henri

Surely, his dream of serenity should show up in a picture of his domestic life, but it doesn’t. Instead, you see Amelie with an erect posture sitting stiffly as she stares hard at him standing before her also stiffly.

Matisse is in his pajamas and Amelie is in a dressing gown, but despite the informal garb, the rigidity of their posture gives off a disturbing tension that casts the scene more as a confrontation than a conversation.

But wait. Matisse does a 180 in “Notes d’un Peintre,” and contradicts his dream of serenity for his painting: “What I am after, above all, is expression. What interests me most, the human figure. It is through it that I best succeed in expressing the nearly religious feeling that I have towards life.”

If only he kept quiet and just painted.