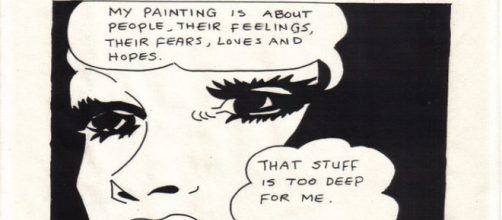

"Critics can be cruel – I should know, I was one of them.” So wrote Ryan Gilbey of the Guardian on Friday (April 27). “Judging art sometimes involves judging people. But there are times when I and other reviewers have gotten unnecessarily personal.” Me, too, Ryan, but I don't feel guilty about it. Art and everything about it is personal. That's the beauty of it. Consider the following true story that occurred about two decades ago.

Taking responsibility

I responded to a published complaint from Sen. George Firestone, a Florida Democrat who served from 1979 to 1987.

He objected to my faulting then-Secretary of State Katherine Harris for allowing a centuries-old painting to peel and flake while in her care. She had borrowed the work from the Ringling Museum, a state-owned treasure house, to decorate her private office. The senator contended that the damage was no big deal because it could be repaired. I said that was like making light of a car accident that put someone in a hospital. While a trauma surgeon may be able to repair the damage, that didn't excuse the one causing the accident. And besides, not all damage is fixable.

Rules of the road

Irreversible damage to art is such an abiding concern to the American Institute of Conservators (AIC) that they established a rule to govern the care of artworks.

“It is important to maintain a proper environment for your paintings. The structural components of a painting expands and contracts in different ways as the surrounding temperature and humidity fluctuates. If maintained in one location at a constant temperature and humidity level, many of the problems requiring the services of a conservator could be prevented.”

Benign neglect

Clearly, temperature control is a biggie in preserving art. Enter, Venus and Cupid at the Forge of Vulcan, an oil on wood credited to the 16th-century studio of Jan Brueghel the Elder” in the Ringling Museum collection. According to the AIC, while paintings on canvas react faster to changes in humidity levels than those on wood, the changes that occur on a wood can cause greater structural damage and therefore requires “conscientious” care.

No such care was taken by Harris. To hear museum conservator Michelle Scalera tell it. climate control records should have been sent to the Ringling every two weeks and they weren't.

Getting personal

Besides neglect, Harris's office broke a state regulation: “Art shall not be loaned when the purpose is not determined to be a definite exhibit.” As I pointed out back then, hanging a five-century-old painting in Harris' private space was self-indulgent. The museum collection belongs to the state and to every Florida resident. The Secretary of State was not entitled to borrow it. I also asked how Harris, a former trustee of the Ringling Museum who holds a fine art degree, would be so cavalier about the care of a painting she borrowed. Was that too personal? You bet it was and I don't take back a word.