Gender politics comes up a lot in today’s art world, and while the 1960s are credited for raising the issue, the drive for equality may date as far back as 1405 when Christine de Pizan penned her book about notable women titled “The Book of the City of Ladies.”

With that book in mind, “The New Woman,” the billing that British art critic Michael Glover gives Gwen John’s portraits of women in 19th century London and Paris, is a misnomer. There is no “new woman.” There is only the awareness of artists who are female that is new.

Stumbling block

And with that awareness and attendant zeal to balance the record comes a pitfall: a tendency to make the male artist the lesser.

Making my point is what Glover said of the painter John Singer Sargent in his review of Gwen John’s show at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, England.

Glover worked up to the Sargent putdown by first praising Gwen and her “dogged opposition” to women being left out the art world in 19th-century London and Paris. He recounted some of the difficulties that she faced when she sought to be a painter like her brother Augustus John.

In figure drawing classes, Gwen found that only male students were permitted to draw from nude female models. Women were also kept from getting around town unless escorted by a male.

Glover makes clear his sympathies with Gwen’s predicament with this sneer: “Perhaps it would be better for a woman to sacrifice herself to the higher interests of family and leave the exploration of creativity to men, who had a much greater natural aptitude anyway.”

So, he cares.

And that’s good until he trips into the pitfall. After describing the lack of adornment in Gwen’s portraits, he says: “She does not show women as unserious, flirtatious temptresses. She is at the opposite end of the spectrum from the preposterously showy John Singer Sargent, who specialized in painting posy, over-dressed, privileged cream puffs.”

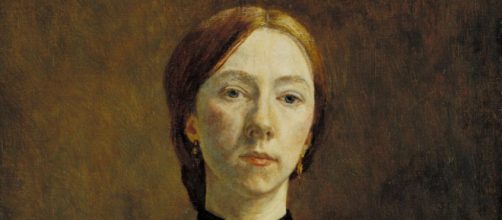

“Cream puffs”? How can this Cambridge-educated art critic say such a thing? Sargent’s portrait of Elizabeth Winthrop Chanler begs the question. What you see is a tense, staring, black-gowned young woman that intimates a sad story. The death of her mother when she was nine followed by her father death, both of pneumonia, left her to care for her seven younger siblings.

And you can see the pain in her eyes.

Then, as a teenager, Chanler suffered an incapacitating curvature of the spine that subjected her to immobilizing treatment for two years. Sargent met her when she was 26 and was moved to paint her.

Sargent said that Chanler had “the face of the Madonna and the eyes of a child.” But he painted her as a troubled child. Her gaze is somber, and there's an undercurrent of unrest. Her right arm leaning on a pillow appears tense.

In plain sight

Yes, Sargent painted society portraits, but to reduce them to “preposterously showy” or “posy, over-dressed, privileged cream puffs” misses his sensitivity to his sitter inner life. You can’t look at Chanler’s portrait and not know that.

It's a fine thing that Glover credits Gwen John the way he does. But it’s not fine that he put Sargent down to do it. And here’s the thing. The look of Elizabeth’s bleak stare and underlying discomfort, along with the limited tonal range in color, bears the unerringly same look of Gwen’s self-portrait.