The new exhibit at the National Gallery in London titled “The Ugly Duchess: Beauty and Satire in the Renaissance” called up a memory of an NPR broadcast about people acting out of character.

The report featured psychologist David DeSteno who cited a growing body of evidence showing that “everyone – even the most respected among us – has the capacity to act out of character.”

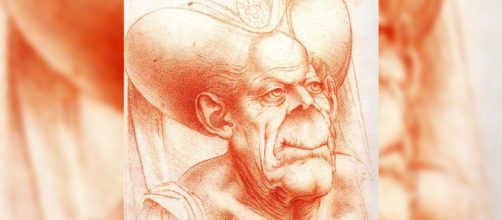

Dr. DeSteno’s words came rushing back when I received news of the National Gallery exhibit of a drawing nicknamed “The Ugly Duchess” by Leonardo da Vinci. The image was completely out of character for him.

Out of the ordinary

How could a Renaissance master given to picture conventionally beautiful women like "Ginevra de' Benci" or "Lady with an Ermine," produce such an unconventional portrait?

Whoever nicknamed this drawing “The Ugly Duchess” had a bias against the aged. This includes Jonathan Jones, art critic for The Guardian who sees the wrinkled old woman in this drawing as “the grotesque, shocking side of Leonardo da Vinci.”

Jones even compared the portrait to the horrors of Francis Bacon. Jones’ take on the drawing is especially odd since Leonardo sketched old men just as wrinkled as “The Ugly Duchess,” and no critic ever called any of them ugly or grotesque.

Perhaps what’s unattractive about the sketch is the horned headdress the woman wears, which is said to be an aristocratic headdress.

Safe to say, this likeness is not one of Leonardo’s conventional portraits.

Another artist in the news with an equally out-of-character work is on display at Christie’s auction house: Henry Moore’s bronze sculpture called “Mother and Child with Apple.”

According to Nicholas Orchard, Christie’s chair of modern British and Irish art, Moore’s sculpture represents “pioneering work.” But the sculpture is far from “pioneering.”

“Mother and Child with Apple” is representational, a style Moor ultimately rejected, preferring the ideal of ancient sculpture, which was about inner spirit rather than outward appearance.

This sculpture is a literal illustration of the title, a line drawing in bronze, rather than Moore’s signature style that looks as if it came from boulders.

Odd that Moore made this sculpture when he was 58 years old, a time when his reputation was well established for what art historian Helen Gardner said in her 1959 book “Art Through the Ages” was work “supercharged with feeling on a grand scale.” There’s nothing grand about “Mother and Child with Apple.”

Romancing the stone

By the time he was 58, his work was nearly abstract, and almost always based on the natural world, such as bones, pebbles.

Even his famous reclining female figures and mother and child suggest landscapes.

And get this, 30 years before Moore modeled “Mother and Child with Apple,” he made a sculpture for the London Underground. Titled “West Wind” with a figure that looked carved out of a mountain, or a memory of rocks worn by the sea.

In his own words, Moore said: “My sculpture is becoming less representational…what some will call more abstract; but only because I believe that in this way can I present the human psychological content of my work with the greatest directness and intensity.”

You don’t get that in "Mother and Child with Apple."