You don't get too many eureka moments when the authenticity of a painting is in question.

It takes technological effort like X-Ray and Infrared analysis. A painting said to be by Salvador Dalí and owned by the Art Institute of Chicago didn't even pass the smell test. It didn't look like anything he ever did.

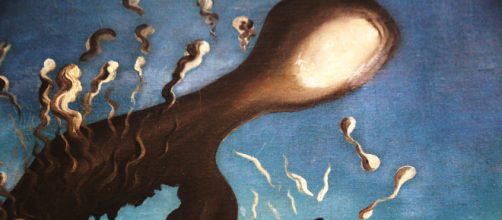

"Mysterious" is the word CNN used to report Dalí's purported painting "Visions of Eternity." Of course, one might ask, isn't all imagery by one famous for picturing pocket watches with the consistency of Camembert cheese dripping over a barren landscape "mysterious"?

Two curators for the Art Institute of Chicago's new show "Salvador Dalí: The Image Disappears" say they were "stumped" by the painting "Vision of Eternity." They never saw anything like it by him before.

Caitlin Haskell and Jennifer Cohen found the "shadowy humanoid figure perches on top of a single arch" a headscratcher. Dalí showed figures standing under an arch ("Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire"), but never on top of an arch, they said.

So, the curators saw "Visions of Eternity" as "out of place" in Dalí's repertoire. As Cohen explained: "We really couldn't find anything like it across his work." One factor is the unusual size - almost nearly seven feet tall.

According to the curators' research, when Dalí painted "Visions of Eternity," he was only picturing small-scale work with many symbols, not the image of a single figure on a lone arch.

Of course, one may ask what's so unusual for Dalí to do something unusual. So, the curators worried about the authenticity of the work. As Cohen admitted: "We were really panicking." (Translation: Did the Art Institute own a fake Dalí?)

The fact that the previous owner, the late Joseph R. Shapiro, was a former trustee to the Art Institute didn't prove anything because the owner before him was unknown. How to confirm the authenticity of the painting without its history?

The eureka moment

But then, Haskell and Cohen found a figure similar to the hunched one in "Visions of Eternity" in another Dalí painting – a mural for the pavilion Dalí designed for the World's Fair in New York in 1939.

In the pavilion, the curators noticed that the mural included Dalí's melting clocks and other familiar tropes.

They also saw the whole "Visions of Eternity" next to the clocks. Problem solved.

But wait. Are you thinking what I'm thinking? Just because "Visions of Eternity" looks like a painting that Dalí made for the World's Fair is not proof that it's his. A reported 20,000 people attended the event – plenty of opportunity for a copycat.

And why isn't anyone at the Art Institute worried about the lack of provenance for "Visions of Eternity"? All the museum has to go on is that one of its trustees owned it. How did he get it? Did Dalí give it to him? Sell it to him? If not, where did he get it from?

As for analysis with Infrared and X-Ray, this was reportedly done, and the results were inconclusive. Look, if I sound suspicious, blame it on Dalí.

After amassing a fortune estimated at $10 million, he sold his signature, kicking off a $1 billion counterfeit-print industry.

Read about it in the 1992 book "The Great Dalí Art Fraud and Other Deceptions" by Lee Catterall.

Will the real Dalí please stand up

The Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg doesn't recognize Dalí prints made after 1980. The auction houses of Christie's and Sotheby's in London refuse to sell Dalí prints, except the early etchings of the 1930s. OK, that's his prints. What of his paintings? With so little detail in "Visions of Eternity," it'd be a cinch to forge.

I'm just saying.