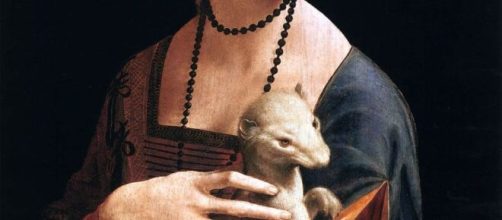

Matching the long history of the “Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani (Lady with an Ermine)” painted 533 years ago, Eden Collinsworth’s new book title is also long: “What the Ermine Saw: The Extraordinary Journey of Leonardo da Vinci's Most Mysterious Portrait.”

The facts of this painting’s life pile up: from the time the Duke of Milan commissioned the portrait of Cecilia (one of his mistresses), to its purchase centuries later by a Polish nobleman, to its theft by the Nazis, to its rescue by the Monument Men, to its final resting place in the National Museum of Krakow.

Art vs. art history

For me, the intriguing part of “Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani” has nothing to do with those who owned it, which is the focus of this book. The image itself warrants a book of its own.

Yet, Amanda Foreman’s book review in the New York Times raves about the history of the painting, calling it “a glorious picaresque of unbridled passions and unmitigated scoundrels, a glorious romp through the great palaces and palazzos of Europe."

But the “romp” seems gossipy. For instance, does anyone really care if the Polish nobleman who acquired this portrait bought it for his mother?

Better than 'Mona Lisa'

“Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani” warrants a book of its own if for no other reason than it’s a better portrait than the one that Da Vinci painted of "Mona Lisa."

Compared to Mona, Cecilia is more luminous and storytelling.

Likely that’s why it took until the 20th century for scholars to attribute the painting to Da Vinci. They didn’t think he painted Cecilia because it is so unlike his other work. For one thing, her figure isn’t set against a landscape or scenery of any kind.

Persuading the scholars is its "contemplative tone," which was Da Vinci’s signature style. There are also multiple glazes – something the painter is known to use to create the illusion of depth. He did the same thing in the Mona Lisa.

Portrait of a weasel?

But if you ask me, the most notable part of this portrait isn’t even Cecilia, it’s the ermine – basically a weasel – in her arms. Why is a weasel in this portrait? This is no little lamb, the traditional symbol of innocence and purity, and revered quality in Christianity.

The ermine is known only for a fetish for cleanliness.

Da Vinci wrote about that fetish in his Notebook, saying that an ermine would rather let itself be captured by hunters than take refuge in a dirty lair and stain its purity. He even made a drawing in pen and ink illustrating the fetish, describing its surrender to a hunter to retain its purity.

But given Da Vinci’s interest in this animal’s purity, and given that it’s a revered quality in Christianity, you might easily conclude that he was a religious man. He wasn’t, not if it meant adhering to ritual. Making this clear is an incident noted in Charles Speroni’s marvelous book “Wit and Wisdom of the Italian Renaissance.”

According to Speroni, a professor emeritus of the College of Fine Arts, UCLA, the incident went something like this: On a Holy Saturday, a priest made the rounds of his parish, as was the custom, blessing homes with holy water.

When he came into Da Vinci’s room and sprinkled holy water over one of his paintings, the painter angrily asked him why he was getting his painting wet.

The priest said that it was the custom and that it was his duty to carry it out. He added that he was doing the right thing: “It is God’s promise that for every good thing one does on earth, one will receive a hundredfold from above.”

When the priest left his house, Da Vinci went to the window and threw a large bucketful of water on top of him, saying, “Here is hundredfold that is coming to you from above, as you said you would get for the good you were doing me with your holy water, which ruined half of my paintings.”