Recent marketplace news became an unintended art lesson on how literal imagery can be vague, and metaphor can be a gut punch.

First, the news: GameShop, a video game retailer selling NFTs of "Falling Man," lifted from Richard Drew's real-time photograph of a man leaping to his death from the WTC on 9/11, has been taken off the market. The buying public rejected the idea of profiting from tragedy.

Likely the public also knew that the story of 9/11 was not a picture story. You cannot see the 2,606 victims pulverized into dust.

The canceled sale of "Falling Man" isn't the first time a figurative allusion to the WTC catastrophe has repelled the public.

Twenty years ago, a sculpture by Eric Fischl called "Tumbling Women" – an upside-down female in free-fall from a leap from the 110-story tower – outraged New Yorkers on seeing it displayed at Rockefeller Center. It had to be taken out of sight.

Fischl said in a statement that he meant to show "sympathy for the vulnerability of the human condition, both specifically towards the victims of Sept. 11 and towards humanity in general."

And he wrote a poem to that effect that appeared on a plaque by the sculpture with words like, "People we love/began falling." Alas, the poem was as literal as his sculpture. When you get too specific, you miss the big picture.

Metaphors add meaning

The Rockefeller Center installation of "Tumbling Woman" occurred in 2002.

Yet, even 15 years later, all bets were still off in artworks showing anyone leaping out of the Twin Towers.

An all-media exhibit called "Age of Terror: Art Since 9/11" at London's Imperial War Museum even made a point of steering clear of anything to do with the 9/11 horror.

As far as I can tell, when it comes to memorializing that horror, the only art form that captures it without pictorializing it is the metaphoric WTC Memorial created by architect Michael Arad.

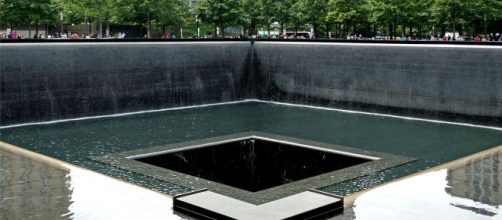

I'm talking about "Reflecting Absence" – the twin reflecting pools in the size of the gaping holes left by the collapsed towers. Without bodies to put to rest, Arad opted to create the look of empty graves. The concept bested all other ideas submitted by 5,201 other architects from 63 nations.

Living in Manhattan's East Village, Arad told me in a phone interview that he witnessed the towers come down. The sight upended him, and it took him a year to conceive of "Reflecting Absence."

In Memoriam

Arad shared his hopes for the memorial: "I want people to stand at the edge of these voids, experience their space surrounded by the names of those who died, and have a true memorial." You get that from the two cavernous holes in the ground, not from a figure jumping out of a window.