“Reframed: The Woman in the Window,” the new show at London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery – sculpture, painting, photographs, and film – is getting rave reviews.

Rave reviews

"Bracingly intelligent" – the Daily Telegraph, "Delightfully inquisitive" – The Times, "Enthralling, imaginative and constantly surprising" – The Observer.

It’s peculiar, though, that Rembrandt’s “Girl at a Window” is on the list of exhibit examples. Can it be that Dulwich Gallery makes no distinction between a child and an adult?

In an essay about “Girl at a Window,” the gallery's assistant curator Helen Hillyard called the “girl” a “young woman.” This, of course, allows her to include the painting in a show about women in windows.

But later in her essay, Hillyard makes a clear distinction between child and adult by refuting a commonly held view that the figure in Rembrandt’s picture is Henrickje Stoffele, the woman he took as his mistress after the death of his first wife.

Hillyard argues that the model couldn’t have been Stoffele because she was 19 when the painting was made – “perhaps too old to be the girl,” she added. “Perhaps”? One may well wonder why she even bothered to include “Girl in a Window” in the first place.

As for the identity of the girl in Rembrandt’s painting, isn’t she the same one in his painting “Girl with a Broom”? Why hasn’t anyone noticed the similarity, down to their clothing?

In her 1964 book “What is a Masterpiece,” art critic Charlotte Willard gauged the age of the figure in “Girl with a Broom” as 10 years old.

She also identified her as a servant. If she’s the same figure in “Girl in the Window,” we’re talking about a pre-teen servant girl with eyes that speak of a hard life.

Identity crisis

In both of Rembrandt’s paintings, you see a figure on a work break. In “Girl in the Window,” she has left her labors to lean on a window ledge, as if to take in fresh air. In “Girl with a Broom,” she has left her labors to take a drink of water. In both paintings, her eyes are no longer innocent.

Showing with Rembrandt’s “Girl in the Window” are photos of performance artist Marina Abramovic taking the place of a sex worker in Amsterdam’s Red-Light District.

Can that be why Naomi Polonsky, a London-based art critic sees "undertones of sexual availability" in this show?

If she’s right, where in the world is that undertone in “Girl in a Window”?

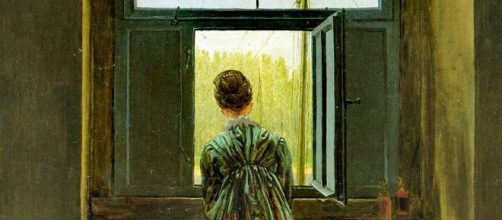

As packed with meaning as Rembrandt’s painting is, a painting on the exhibit theme even more packed is “View from the Window” by Caspar David French.

What you see is a view of the back of the artist’s wife Caroline bent forward as she looks out an open window overlooking the Elbe River in Dresden. Partially visible in the distance are masts of tall ships.

Seen from the back, you don’t get Caroline’s reaction to what she sees. You only get Caspar’s reaction to his wife looking out a window, his sense of her longing, perhaps of boarding a passing ship and sail away. So what you get is the artist’s uncertainty, his insecurity.

When the Daily Telegraph praises this show as "Bracingly intelligent," it's French's “View from the Window” that makes the case.