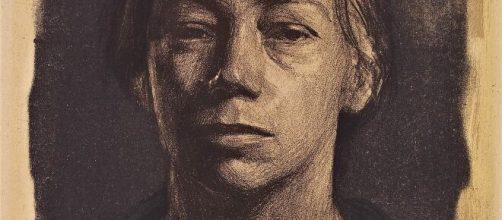

I can't think of a better incarnation of present-day unease than Kathe Kollwitz’s 1904 self-portrait, a lithograph newly acquired by the Museum of Modern Art.

Puffy eyes, as if from sustained sobbing, stare out from a murky air that presses in on her. Rendered more than a century ago, Kollwitz’s image could have been made this morning in our divided world worn down by one argument after another.

Kollwitz is known for raging against war and poverty. Aren’t we still doing that, too? You can see those themes everywhere in her work, and even in her 50-plus self-portraits.

A typical Expressionist, Kollwitz shows how an experience feels rather than how it actually looks.

Her picture titles say a lot about her sympathetic stands for laborers and their working conditions. Portrait of a Woman Worker with Blue Shawl emphasizes her sympathy with an isolated image of a worn-down figure - not unlike her self-portrait.

The disasters of war

Kollwitz was also a pacifist, having lost a son in World War I and a grandson in World War II. Such life events also show in her picture titles, like "Woman Welcoming Death," "Cycle of Death," and "Death and the Mothers."

With scratchy lines that conjure the sound of fingernails scraping across a blackboard, "Killed in Action" conveys the tragedy of a life lost to war. What you see is a mother overcome with grief on hearing of her husband’s death as her children clutch at her with fear at the sight.

In her "Diary and Letters of Kathe Kollwitz," she tells of using her son Peter as a model for "Killed in Action": “I drew myself in the mirror while holding him in my arms…

The pose was quite a strain, and I let out a groan. Then he said consolingly in his high little voice: ‘Don’t worry, Mother, it will be beautiful, too.’”

Weight of the world

While known for portrayals of workers suffering inhuman conditions, her pictures of personal grief are the most despairing. Making clear her experiences were a compelling force in her art, Kollwitz recounts in her diary a night that her ten-year-old son Hans nearly lost his life to diphtheria:

“An unforgettable cold chill caught and held me: It was the terrible realization that [at] any second this young child’s life may be cut off, and the child gone forever.”

The Nazis saw Kollwitz’ work as a social protest and banned an exhibit in 1937.

But art lovers found their way to the show anyway. Check out this reminiscence from Mina and Arthur Klein’s book “Kathe Kollwitz: Life in Art”:

“If someone came into the shop asking for the Kollwitz exhibit, he was told that unfortunately it had been closed - but the artwork was still upstairs in the gallery. Silently, one by one, the visitors approached the drapes, moved them aside, climbed the small stairway, and looked at the works of their great blacklisted friend.”

MoMA owns 34 other works by Kollwitz and is planning a major exhibit of them. Christopher Cherix, the museum’s chief curator of drawings and prints, said in a statement, “Käthe Kollwitz’s legacy looms large over the 20th and 21st centuries.” Current events make that factual.