"The Godfather," Francis Ford Coppola's 1972 film, adapted from Mario Puzo's novel about a Mafia Crime family, is 50 years old and, like all works of art, needs a facelift – restoration to its original distinction.

Distinguishing characteristic

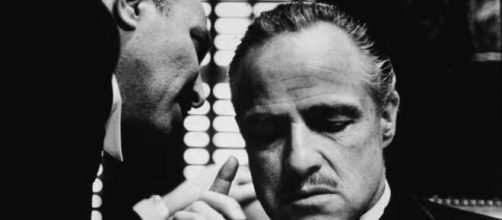

A large part of that distinction has to do with the film's shadows. The play of dark and light is as key to this film as it was to the paintings of Caravaggio. (More about that in a moment).

In an interview reported by the New York Times, Coppola said the movie needs restoring because Paramount Studio made so many prints from the original negative to meet the demand worldwide that "it wore out something awful."

How important are the shadows in "The Godfather"?

Let me count the ways. The tale takes place over ten years. Scenes were filmed in New York, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, and Italy and with numerous characters. The shadows hold it together with the ongoing pattern of strong dark and light.

When asked how he knew when there was too much darkness or not enough, Coppola pointed to the first scene in Don Corleone's office, which he said he made "really dark. That was deliberate."

Good vs. evil

The heavy shadows also conveyed the idea that extremely shady things were going on in Don's office. That's where he utters the now-famous line, "We'll make him an offer he can't refuse."

James Mockoski, Coppola's film archivist and restoration supervisor, who joined him in the interview, said that some wanted more light in the scene:

"You've got this beautiful opening, and they want to see all the details and the wood paneling.

Well, that's not the point. That's not 'Godfather.'" Coppola added, "Any really thoughtful person knows what's important in the frame."

Given the importance of shadows in this movie, credit must go to Gordon Willis, "The Godfather" cinematographer, who used blackness to express the dark side of the characters in the film.

What Willis achieved in "The Godfather" is comparable to what Caravaggio achieved in his 17th-century paintings. Like the painter, the cinematographer left a lot of scenes, lost in the blackness of heavy shade, to the imagination.

The darkness is meant to underscore the evil Caravaggio pictured. Blacking out of parts and sparsely lighting others has another effect: stark contrast intensifies the drama.

Power of a painting

Not to take away from the moral conflict between good and evil that marks "The Godfather," I submit there's another film that better signals the power of a Mafia crime family.

You see this power without a single shot fired in the 1990 comedy "The Freshman." Marlon Brando is playing mafia boss again, this time as Carmine Sabatini.

And on a wall over this Don's living room fireplace hangs Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa - the original painting. When asked about the one in the Louvre, his daughter explains that the museum owns the copy. Now that's clout!

While there are no paintings featured in "The Godfather," there's no need. The film is a painting all by itself.