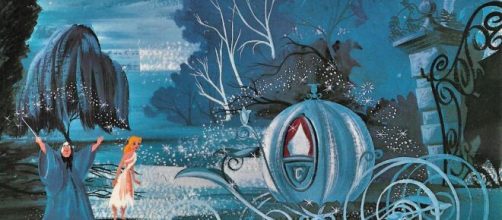

You don’t expect a museum known for its massive art collection from classical antiquity to Old and Modern masters to pay attention to the animated cartoons of Walt Disney like "Cinderella" or "Beauty and the Beast."

Au contraire

A Metropolitan Museum of Art’s show makes it evident that Louis XVI’s taste in decorative arts (also known as Rococo) seen at Versailles, held sway over the creator of Mickey Mouse.

Not Disney alone. The French king’s love of extravagant embellishment at Versailles attracted 18th-century painters who were sick of the heavy, histrionic look of 17th-century picture-making that preceded them.

Art Daily, reporting on the Met show, noted how the flashy, fanciful Rococo style tied to the American cartoonist famous for amusement parks. Plainly, the 18th-century art style’s less weighty approach was made for Disney.

You can see what Artdaily calls Rococo’s “colorful costumed court life laced with lavish floral wreaths, delicate scroll-like curves, soft pastels” nearly everywhere in Disney’s resplendent movie scenes. How did I miss that?

“Beauty and the Beast” exemplifies the point of the Met show. Belle dances the light fantastic in a castle full of objects that look straight out of Versailles including an ornate candelabra, teapot, and pendulum clock.

It’s as if Disney purposely took the frivolous look of Rococo painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s palace decorations, visible on ceilings and walls, to give his cartoons fluency and theatrical flair.

Like Tiepolo, Disney pushed art out of its Baroque shadows into the bright light of the Rococo movement rich with illusions rendered in airy, sunny colors.

When you see the candelabra, teapot, and pendulum clock magically sing and dance in “Beauty and the Beast,” you know it’s not far from Tiepolo’s ceiling painting that describes Apollo Bringing the Bride.

When the Sun God races across the sky in a chariot drawn by white horses, curvy winged cherubs on swirling pink clouds create the ascending, in-flight effect, isn’t that the very stuff of the Magic Kingdom?

Indifference to gravity and reality in make-believe worlds where acrobatic figures appear as light as clouds are standard fare in the work of both the artist and the animator.

As the museum makes boldly clear, Disney’s work is far from figments of his imagination. As Art Daily put it, the genesis “comes directly from the French Rococo.”

It helps that the Met has a lot of Rococo art objects on view to give exhibit goers a chance to see Versailles-like décor: I’m thinking of a mantel clock embellished in 1750 Paris by Jean-Joseph de Saint Germain.

The Met show can have you picturing Disney studying objects like those in the museum collection while planning and sketching the sets for “Beauty and the Beast.”

With the Disney tie in mind, you find yourself envisioning the museum’s ornate bronze clock or wall brackets, likely once adorning a palace or chateau, singing, and dancing along with Belle.

In fact, the mantel clock described by the Met as “undulating scrolls interspersed with floral motifs that are characteristic of French Rococo design at its liveliest,” also describes the palace furbishing in “Beauty and the Beast.”

Who knew?

Laurels to the Met for making the case that Disney’s presumed castles in the air followed the beaten path of a centuries-old art movement. In our crass world, art can use all the credit it can get.