Since Chuck Close died last month, I’ve been meaning to write something.

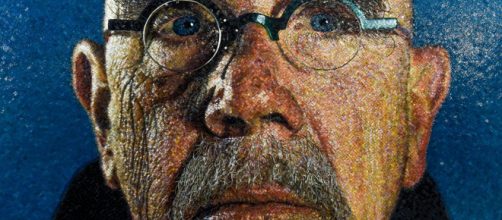

After all, he was an art world giant, a painter, photographer of monumental closeup portraits that began with his own nine-foot-tall likeness that showed every follicle in his unshaved face. He made the old art of portrait painting new.

Taking advantage

But accusations of sexual harassment by several women seeking modeling jobs at his studio held me back. How do you sing praises of a man who debased women? His defense to the NY Times didn’t help.

Close claimed that all he did was talk to women about their bodies to evaluating their modeling potential.

Hyperallergic cited an example; he told a woman that her lower anatomy looked “delicious.” He said, “Last time I looked discomfort wasn't a major offense.” He also said, “I have a “dirty mouth, but we’re all adults.”

Clearly, Close’s offense was “major” to the National Gallery of Art. A show of his work was canceled there in 2018 after accusations of sexual harassment made the news. National Gallery spokeswoman Annabeth Guthrie told the Times that the cancelation was not only for his trash-talking to women but also for asking them to take off their clothes while doing it.

A first

Guthrie said the museum had never before canceled a show for such a reason. All that said, it’s hard to dismiss Close’s work.

For one thing, he’s not the only artist known for sexual misconduct on view at the National Gallery. I’m thinking of the many paintings by Fra Filippo Lippi, an ordained monk who ran off with a nun, Lucrezia Buti, and impregnated her twice.

Lippi’s work, like Close’s, certainly merits display. The Renaissance painter lent faces the most tender expressions. He added to their soft, sensitive aura with pale light and translucent colors. He was a natural, and so was Close.

Drawing a blank

In fact, the way Close made his portraits came out of a neuromuscular disorder from childhood that caused him facial blindness or Prosopagnosia. He had trouble recognizing faces. He drew a blank even with people he knew very well.

He told NPR that the condition drove him to make portraits with his camera because when it came to remembering, he had a photographic memory.

Given that kind of memory, Close was able to break his photos down to one fragment of a face at a time and build them back into a recognizable image. Viewed close up, his faces look almost abstract. But seen at a distance, all the parts come together – not unlike what Seurat did with his pointillism technique.

So, it looks like the only way I could write about Close contribution to the art world is to add on in his misconduct. It’s the same way that Fra Lippo Lippi's accomplishments have been written about since the Renaissance.