LA Times art critic Christopher Knight's review of “King Tut: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh” at the California Science Center raises a question that he clearly didn't intend, otherwise he would have noticed the irony of saying, “Tut is all about the tomb, the afterlife and desperate immortality...” (The question in a moment).

Buried alive

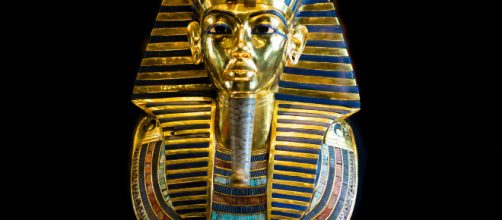

Tut's exhibit examples – his mummified body and jewelry originally wrapped inside the mummy's bandages, plus other personal effects -- are the plundered contents of the boy-king's tomb routinely displayed to the public for the price of admission to museums throughout the world.

The spectacle has bee a cash-cow for exhibit halls ever since Howard Carter, a British Egyptologist, dug up the tomb in 1922. Have you guessed my question yet? No sense keeping you wondering. I'm asking if we are ghouls. Is there a culture on earth that thinks grave-robbing is a good thing?

Out of this world

And Carter didn't just unearth a grave and carry off its contents, he took something else – Tut's afterlife. The tomb was supposed to protect his remains for the world to come -- an Old Nile belief in life after death. The credo was so strong that food and wine were also buried so the dead wouldn't go hungry. Knight mindlessly noted this, saying, “Tut is all about the afterlife,“ without questioning the show that destroyed it.

Instead, he asked other questions. Why, he wondered, is an art and archaeology exhibit on view at a science museum instead of an art museum? As if it's okay to parade the personal effects from a grave as long as the venue is art-y.

The showstopper

Knight also questioned the commercialization of Tut's artifacts, but again, didn't stop to ask why they're on display in the first place. He only said that the relics were “overly theatricalized.” And here's the kicker. He called the life-size figure of Tut's sentinel, whose job it was to protect him for his afterlife, the “showstopper.” He marveled at the jet-black eyes “staring toward eternity,” and missed the irony of what he was saying: the guard wasn't on the job; he was showboating in a California museum.

Of course, Knight isn't the only one oblivious to the meaning of Tut's tomb. When Thomas Hoving, former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, sought to show the Egyptian relics, his focus was on the money it would make the museum. In his 1993 memoir “Making the Mummies Dance” (the title alone makes my point), he wrote, “I had spent the night calculating what revenues might be gained from the sale of a wide variety of books, calendars, jewelry, reproductions, posters, slides and cassettes..."

Hoving, who had earned a doctorate in medieval objects, wrote that the big business aspect of the Tut show was the “high point” of his career at the Met. “Afterwards, slowly and almost imperceptibly, I became more and more bored with the museum...Tut kept me going.” Hoving forgot that it was King Tut who was supposed to keep going.