Unless the word “joyously” has a different meaning in England, British art critic Jonathan Jones got it wrong when he wrote in the Guardian on Dec. 3 that the Royal Academy’s new show Dali/Duchamp is a “joyously mind-expanding art explosion for the holidays.” Work by this pair is not the stuff of celebration. One of them was a Surrealist and the other a Dada-ist and neither conjure up “the season to be jolly.” Instead, their art came from a dark place – the horrors of war.

War is hell

The term Surrealism stems from the French word, surreel, defined as surpassing the real.

Artists working in this movement set out to free images from their customary settings and reset them in ways that purposely made no sense. Theirs was an insurrection against the reality that brought WWI, so they concocted their own reality. Surrealism, and its offshoot Dada, then, was a kind of war against Western civilization. And as with all wars, there were many fronts. Some artists tried a kind of automatic writing, creating forms without conscious thought. Others practiced Dada (Duchamp did this) -- derived from the French meaning baby talk or gibberish, to escape the dehumanization of war. Then there’s Salvador Dali, who pictured nonsense as if it were real.

Say cheese

Art dealer Julian Levy quotes Dali defining his art in his memoir ”The Conquest of the Irrational,” saying, “My whole ambition in the domain is to materialize the images of concrete irrationality with the most imperialist fury of precision.” Translation: He painted pocket watches to look like they were melting cheese, which sent a slew of messages: In a world that brings death through war, time comes to a halt and all that’s left are decomposing tree stumps on an otherwise deserted earth where the only survivors are ants.

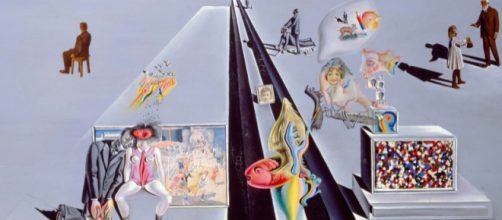

So much for Jones calling the Dali/Duchamp exhibit a “joyously mind-expanding art explosion for the holidays.” To be fair, he was referring to Dali’s “The First Days of Spring.” But this painting, like all his work, is vintage Surrealism – screwy from start to finish.

Dressed to kill

Even when Dali designed a window display for Bonwit Teller department store (the one Trump demolished to erect Trump Tower), it was about death and destruction. He posed a mannequin outfitted in a Bonwits’ dress lying in a bathtub. But when he wasn’t looking, the department store management lifted the mannequin out of the tube to model the dress standing up. Dali had a fit, which sent the bathtub smashing through the plate glass window to the sidewalk.

Happy holiday

Equally bent on changing the way the world sees itself, Marcel Duchamp was also set on ruination. For instance, he added facial hair to a reprint of Mona Lisa with a mustache and goatee and called it “Shaved.” Clearly being anti-war meant making non-art. The point these artists were making is understandable. Calling their work holiday fare isn’t.