He’s probably the most famous Man in the world (sorry, Donald), thanks to Leonardo Da Vinci’s iconic ink drawing from the 1490’s called “Vitruvius Man.” Of course, there was no such man. He lived only in the mind of the first century B.C. Roman architect Vitruvius, who imagined the figure’s perfect proportions. Da Vinci’s drawing sought to prove that ideal by extending the arms and legs out to a perfect circle and square enclosing them. He also rendered the figure in the buff, likely to make the model ratios between limbs and torso more clear.

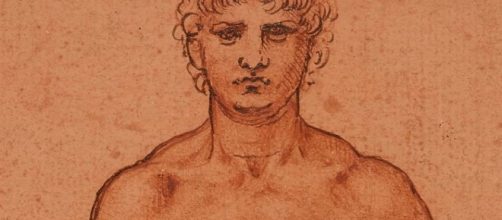

The perfect man on display in all his glory

Far less known is Da Vinci’s drawing of the same figure called “Nude Man,” except all the appendages are at ease and short of the circle or square interrupting the view. That very directness of the figure, without anything else in the drawing to divert attention from the figure’s anatomy, gives the impression of a medical drawing. It popped up in the news last week when The Guardian, a London daily, did a riff on this lesser known Da Vinci work. Consider today’s column my riff on it.

Truth and beauty in the raw

“Nude Man, drawn in the Renaissance when the study of nature and man’s natural state went together, didn’t raise any eyebrows. But the centuries that followed, including ours, speak of a public less tolerant of nudity in art; although to Queen Elizabeth’s credit, “Nude Man” is held in the Royal Collection.

The church, on the other hand, has never been comfortable with the bared bodies in Renaissance art. When Michelangelo’s painted the “Last Judgment” on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel and filled it with exposed anatomy, Biagio da Cesena, a Vatican official, wanted every birthday suit covered with draperies in the belief that nakedness is shameful and is only appropriate in paintings that describe martyrdom or humiliation. The Pope didn’t agree. Seeing the human form in all its glory as divine, he ordered that the painting remain intact.

Tradition with a twist

All bets were off after Michelangelo died and a new Pope ordered every unclad figure be cloaked. That squeamishness about exposing flesh in art has also continued outside of the church.

And as controversial as picturing nakedness is, it got extra contentious in 2001 when New York lens artists Renee Cox added two extra layers to people’s discomfort – that of race and gender bias. One of her photographs on view at Brooklyn Museum titled “Yo Mana’s Last Supper,” conveyed her view of patriarchy and racism. “Why can’t a woman be Christ?” she had asked. “We are the givers of life!” Other of her works posed similar challenges, like a black Virgin Mary and a crucified Christ as a black man. Defying church doctrine is vintage “Vitruvius Man”. The rest of her defiance is the lesson for out time.